Lurching Towards a Canon

Mahāyāna Sūtras in Khotanese Garb

The concept of canon centers around authority. Assertions about canonicity both reflect and reshape the structure and the source of authority. In a Buddhist context, processes of canonization are highly fluid and complex, shedding light on the socio-religious landscapes of different Buddhist cultures. The present essay explores the complexities of canonization by focusing on a specific Buddhist culture on the ancient Silk Routes, where Mahāyāna sūtras, a collection of Buddhist literature of disputed authenticity in India, were accepted as scriptural and canonized in a remarkable manner. Through the lens of an indigenous Buddhist poem, the author argues that the reception and canonization of Mahāyāna sūtras give illuminating clues about a pivotal transition in the history of this Buddhist kingdom named Khotan, where both the removal and the bestowal of authority took place.

authority, canon, canonization, Central Asia, Mahāyāna Buddhism, tradent

Introduction

Buddhists, as is the case with adherents of many other religions, establish and stabilize their collective identity among other things through the (re)production of a particular body of literature deemed authoritative. Across the Buddhist world, this body of literature is variously designated as “The Pāli canon,” “the Chinese canon (dazang jing 大藏經),” “the Tibetan canon (i.e., Kanjur and Tanjur),” etc. Carsten Colpe advanced the proposition1 that the Buddhist ‘Three Baskets’ (Sanskrit tripiṭaka, Pāli tipiṭaka) and the Hebrew Bible (acronym tanakh) represented the two independent forms of canonization in human history which became a model for all other processes of canon formation, bringing forth the Christian Bible, the Daoist canon, the Islamic Qur’an, etc. To what extent this claim does justice to the historical complexities of the ‘Three Baskets’2 must remain open to discussion. But it alludes to the significance of the issue of canonicity that persists throughout the history of Buddhism and has great implications for a diversity of Buddhists in different cultural spheres.3 The present essay is a preliminary attempt to tackle the complexities through a case study, i.e., the reception of Mahāyāna sūtras in fourth- and fifth-century Central Asia.

Before delving into the case study, a few remarks on the concept of ‘canon’ are in order. Scholars of Religious Studies have long been working with the theoretical twofold typology4 of an “open canon,” i.e., a collection of authoritative texts in the general sense which does not exclude other texts from canonicity, and to which other texts of equal importance may be added at any time; and a “closed canon,” i.e., an exclusive collection of authoritative texts, to which only scriptural authority is assigned (and no others!). The borderline between the two kinds of canon is not ironclad and stable, but is porous and dynamic. An open canon can be ‘closed’ in some sense by separating the canonical texts from the apocryphal and by calling a halt to the addition of new texts into the collection. The act of closure, which forms “[t]he most important step toward canonization” (Assmann 2011, 78), does not, as it were, draw a line in the sand because its binding force is not permanent and its consequences are not irreversible. On the other hand, even if no new texts may be added to the body of literature, this does not necessarily imply the closure of the canon on the interpretative level, insofar as innovation de facto continues by dint of interpretative text production (e.g. translations, commentaries, etc.; Silk 2015, 6). The further the process of interpretation advances, the more difficult it becomes to standardize or harmonize the texts thereby produced.

Therefore, the utility of canonization as a “contra-present”5 bulwark against the tide of innovation should not be taken literally. Viewing the history of Buddhism in the longue durée, we observe that an open canon is the norm, while a closed canon merely occurs at one or two times and places, contingent on specific historical and socio-religious circumstances of a given milieu which make its closure desirable.6 On the surface of it, there seems to be an asymmetrical relation between these two kinds of canon: The vast majority of Buddhist canons exhibit a greater or lesser degree of openness, whereas closed canons stricto sensu are few and far between. This asymmetry, however, does not mean that the gravitation towards the closure of a canon is incapable of acting as a counterweight to its opening up. On the contrary, a closed canon remains an attractive option even in a Buddhist milieu whose canon is by and large open, and where attempts are made to seal off the body of authoritative literature in some sense. This is all the more the case when the very milieu is in a transitional phase of its history which entails redistribution of religious authority, as will be explained in detail below.

Khotanese Shift to the Mahāyāna

The emergence of a group of authoritative texts designated ex post facto as ‘Mahāyāna sūtras’ around the turn of the Common Era7 is a historical phenomenon which still evades any conclusive explanation. Despite their heterogeneity that renders any attempt at monothetic definition futile,8 Mahāyāna sūtras, especially those belonging to the earlier strata of this body of literature, are more likely to be subjected to skeptical scrutiny as regards their canonical status compared to the sūtras transmitted by the Mainstream9 schools. Disputations about their authenticity were initiated early on by the followers of the Mainstream tradition,10 to whom the texts were unheard of in the Dharma that had come down to them. For this reason and others, the historical argument serving as the basis for the criterion of authenticity or canonicity was not in favor of Mahāyāna sūtras of later historical provenance, and was thus utterly rejected by Mahāyāna scholastics such as Vasubandhu (fl. fourth century CE) (Cabezón 1992, 228). The early advocates of these sūtras were, in all likelihood, educated monks, or rather communities of such monks, who constituted “a number of differentially marginalized minority groups” (Schopen 2000, 24) struggling for recognition. Their struggle, to our knowledge, did not succeed in Middle-Period India to any significant extent.11

The marginalized status of the Mahāyāna in a highly competitive environment might have been one of the motivations for an overland exodus from India.12 It indeed happened. In the late second century, a number of Mahāyāna sūtras surfaced in Central China in the person of an Indo-Scythian missionary.13 This earliest known instance of cross-cultural transfer of Mahāyāna sūtras is probably the result of “long-distance transmission” rather than “contact expansion,” as Erik Zürcher plausibly argued (Zürcher 1990, 158–82). In other words, their mode of diffusion is not reliant on residential monasteries established near prosperous regions or supported by high-level patronage, but consists in incidental and intermittent nodes of communication which are connected through the agency of itinerant monks via transit zones over great distances. In the case of the earliest Mahāyāna sūtras in China, the Tarim Basin seems to have served as such a transit zone, which was not yet capable of affording monastic Buddhism in the late second or early third century.14 The absence of established monasticism also implies that there was no institutional establishment of any Mainstream school. This vacuum created unprecedentedly favorable circumstances under which Mahāyāna sūtras could take root among recent converts to Buddhism in local society and jockey with their Mainstream counterparts for canonical authority—a privilege they had never enjoyed in India.

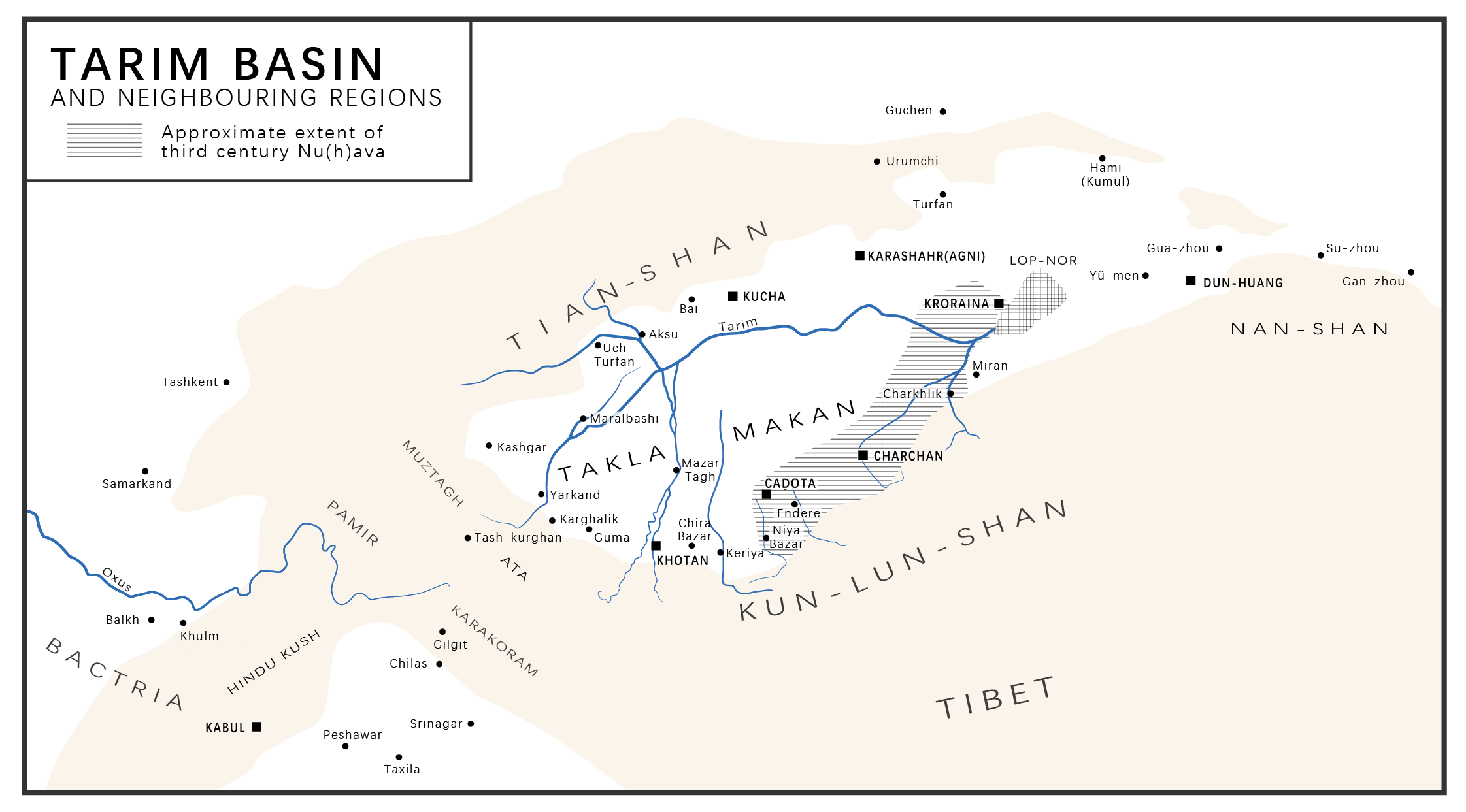

It is in this historical-geographical setting that Khotan, an oasis kingdom situated on the southern rim of the Tarim Basin (Fig. 1), comes into focus. The Iranian ruling élite of the kingdom was so eagerly in pursuit of Indian identity that the kings adopted an Indic honorary epithet (Sanskrit Vijaya, Khotanese Viśa’),15 and that the legendary foundation of the kingdom was anchored in the legend of the Mauryan king Aśoka (Yamazaki 1990, 55–80; Mayer 1990, 37–65). Although multifarious ties with India for long-distance trade and cultural exchanges should render the introduction of Buddhism a matter of course, we know next to nothing as to how Buddhism began in Khotan. As a matter of fact, no archeological evidence for the presence of residential monasteries in Khotan before the late third century has so far come to light.16 To be sure, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence; but one may at least infer from the evidential vacuum that monastic orders affiliated with Mainstream schools, even if founded in Khotan at that point, did not gain any great social prestige or visibility.17 This inference, on the other hand, implies that Mahāyāna monks were provided with a golden opportunity to make forays into the religiously virgin soil of Khotan, where the authenticity of Mahāyāna sūtras, however, may not have gone uncontested.

Zhu Shixing 朱仕行 (203–282),18 a Chinese monk aspiring to the Mahāyāna, travelled westward in search of Mahāyāna sūtras. Around 260, he procured at Khotan an Indic manuscript of the Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā, one of the most influential Mahāyāna sūtras of all time. As he was about to have the manuscript sent back to China, he met great opposition from local monks who were adherents of Mainstream Buddhism. The dispute over the fate of the manuscript was resolved in a highly dramatic fashion, according to the Mingxiang ji 冥祥記 ‘Signs from the Unseen Realm’ by Wang Yan 王琰 (late fifth century):19

Most of the monks and laymen of the Western Regions practiced the Lesser Vehicle, and when they heard that Shixing sought the Mahāyāna sūtras, they all thought it strange and did not give him the texts. They said, “You do not know the correct Dharma, and these will lead you astray.” Shixing responded, “The sūtras say that after a thousand years the Dharma will spread eastward. If you doubt that this was the Buddha’s saying, then let us test it with the utmost sincerity.” With that he set afire a pile of wood and poured oil over it. When the smoke and flames were at their peak, Shixing picked up the sūtras and, weeping and bowing his head, uttered the vow: “If these sūtras emerged from the golden mouth (i.e., spoken by the Buddha), they should be disseminated and spread across the land of Han (i.e., China). Let all the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas bear witness!” With that he threw them onto the fire, causing it to flare up brightly. When the smoke had cleared, it became evident that the words of the texts were all intact, and the birch-bark leaves were as before. The entire nation reacted with joy and reverence. So he stayed behind to become a worthy recipient of offerings. (Campany 2012, 75–76, with modifications)

This episode is intriguing in many respects. It is perhaps for the first time in the history of Buddhism that the ordeal by fire had the final say on the issue of a text’s controversial authenticity.20 More remarkably, the disputation allegedly occurred in a sphere of patrons or faith community, which showed no favor to any specific strand of Buddhism, whether Mahāyāna or Mainstream. This appears to be in tune with the aforementioned inference drawn from archeological data. It remains unclear how much weight should be attached to this episode, the historicity of which was already questioned by Zürcher (Zürcher 2007, 63). The possibility that it was related, in China, with exaggerated unction and thus contains fictitious elements cannot be excluded, insofar as Mahāyāna polemic against Mainstream opponents was a beloved literary trope in early Medieval Chinese Buddhism which often has no basis in historical fact.21

Be that as it may, there is circumstantial evidence suggesting that the episode is based on some source of greater antiquity.22 Even if we are dealing with an example of the Chinese imaginaire,23 not everything of the imaginaire is a figment of collective imagination: At least the conviction that Mahāyāna sūtras had not yet caught on and the fact that their authenticity was still subject to doubt in Khotan by the late third century may not be entirely unfounded in reality. This stands, however, in stark contrast to what Faxian 法顯 (d. ca. 420),24 one of the most renowned Chinese pilgrim-monks, claimed to have witnessed in Khotan at the very beginning of the fifth century:25

This country (i.e., Khotan) is prosperous and happy; its people are well-to-do […] The [monks] number several tens of thousands, most of them belonging to the Mahāyāna. They all obtain their food from a public fund […] The ruler of the country lodged Faxian and his companions comfortably in a monastery, called Gomatī, which belonged to the Mahāyāna. At the sound of a gong, three thousand priests assemble to eat […] The monks of the Gomatī monastery belong to the Mahāyāna, which is deeply venerated by the king; and they take the first place in the procession of images. (Giles 1923, 4–5, with modifications and omissions)

The monastery of Gomatī (aka. Gomatīra),26 consisting exclusively of Mahāyāna monks, represents a new order of Khotanese Buddhism, as distinguished from Indian monasteries affiliated with the Mainstream schools. The foundation of this monastery cannot be historicized with certitude,27 but its continued presence in Khotan as the foremost monastery under royal patronage up to the end of the tenth century is borne out by Khotanese documents from Dunhuang.28 In such a kingdom as depicted in Faxian’s eyewitness account, it would be utterly unacceptable to subject any Mahāyāna sūtra to a fire-ordeal. Furthermore, it is conceivable that knowledge about Mahāyāna sūtras, and a fortiori manuscripts of Mahāyāna sūtras, must have become valued cultural capital such that most Buddhists in that kingdom were eager to avail themselves of. The rigid demand for Mahāyāna sūtras naturally triggered the proliferation of their translations in the local language, as will be shown below. On balance, there seems to have been a historic transition between the late third century and the fifth century, in which the kingdom of Khotan, especially its ruling élite, shifted to the Mahāyāna.

Beginning and End

A not altogether speculative theory on the religio-historical landscape conducive to the Khotanese shift to the Mahāyāna is beyond our reach,29 since we are relatively ill-informed about the time period in question, which is, for the most part, shrouded in darkness. In the course of the fourth century, Khotan receded almost entirely from the vision of Chinese historiographers, since little is known apart from sporadic records of tributary envoys dispatched by the Khotanese kings.30 The kingdom, it seems, remained a vassal state pledging its allegiance to various rulers, Chinese and Proto-Tibetan alike, who in turn wielded hegemony over the Hexi corridor and governed the Tarim Basin on a loose reign. The southward relocation of the kingdom of Nu(h)ava31 in the late fourth through the fifth centuries, probably due to an advancement of the desert, marked “a dividing point in Central Asian history” (Brough 1965, 611). This resulted in the desertion of the major towns of Caḍ̱ota and Kroraina and the breakdown of the southern Silk Route, which, though not entirely going out of use, never recovered its former vitality and was superseded from the fifth century onward by the northern route (Vaissière 2005, 123). In other words, the kingdom of Khotan lost its eastern boundary as well as a long-standing shortcut to Dunhuang and northern China. What consequences the changing geopolitical circumstances had in the socio-religious domain remains to be plumbed.

It may not be simply fortuitous that the kingdom of Khotan began developing a local literacy along with the rise of the Mahāyāna at about the same time as the kingdom of Nu(h)ava was in decline, where a different type of Buddhism had been prevalent. Some documents written in a Gāndhārī-based chancellery language, which fell into disuse in the aftermath of the kingdom’s leaving the Tarim Basin, convey a noteworthy image: Buddhists in third- and fourth-century Caḍ̱ota “worshipped stūpas and bathed Buddha images but recorded few, if any, texts” (Hansen 2004, 306), and local clerics “lived at home with their wives and children, owned property, and donned Buddhist vestments only for occasional ceremonies” (Hansen 2004, 279).32 Although two Nu(h)avan dignitaries had claimed to have “set out in the Mahāyāna” (mahāyānasamprasthita),33 they hardly seem to have done anything beyond paying plain lip service to their Mahāyāna devotion. As Faxian, the aforementioned pilgrim, sojourned at Kroraina in 399, he saw the end of a debased form of the Śrāvakayāna, which stood in stark contrast to the state of affairs in coeval Khotan:34

The king of this country (i.e., Nu[h]ava) has received the Dharma, and there may be some four thousand and more [monks], all belonging to the Lesser Vehicle. The common people of these countries as well as the clergy practice the Dharma of India, but to a greater or lesser degree. (Giles 1923, 2–3, with modifications)

There was no Mahāyāna institution whatsoever, at least not that Faxian was aware of.35 The Buddhist cult entrenched in Nu(h)ava was in many respects different from the Mahāyāna in Khotan, but one of the most salient distinctions between the two Buddhist cultures was highlighted by text-centeredness, namely, the significance of texts in the midst of the faith community.36 In Nu(h)ava, religious authority did not hinge on expertise in authoritative texts, but was rooted in the clergy’s ordained roles in rituals and cultic activities: For the failure to attend communal ceremonies or to put on proper vestments on such occasions, fines (in bolts of silk) were stipulated;37 but there was virtually no trace of any normative statement as to the literary learning of a monk-priest, whose life as a householder made it rather difficult, if not impossible, to cultivate textual expertise. In Khotan, however, it was the other way around: According to Faxian quoted above, Mahāyāna monks in this “ideal civitas buddhica” (Deeg 2005, 86) enjoyed high-level patronage since no later than the early fifth century. Hence there are good reasons to believe that they, under the auspices of “a public fund,” had the time and leisure to seriously engage in textual study and scholastic discussions, which were as important as, if not more so than, their ritual obligations.

The text-centeredness of the Mahāyāna community in Khotan is otherwise corroborated by chance-finds of manuscripts written in a local variety of the Brāhmī script, probably dating back to the fifth and sixth centuries (i.e., Early Turkestan Brāhmī; after Sander 2005, 137–38). Many of these manuscripts are copies of Mahāyāna sūtras in Sanskrit,38 bearing witness to the wide range of knowledge on Mahāyāna literature which was accessible to educated monks at home in Sanskrit. A heptad of Mahāyāna sūtras appears to have been particularly well-received, as is evinced in fragments of their Khotanese translations which can be ascribed to the same time period on paleographic grounds (Skjærvø 2012, 118–19): the Anantamukhanirhāradhāraṇī (Loukota 2014, 13–27, 57–59), the Bhaiṣajyagurusūtra, the Ratnakūṭa (aka. Kāśyapaparivarta; Skjærvø (2003), 409–420; Maggi (2015), 101–143), the Saṅghāṭasūtra,39 the Śūraṃgamasamādhisūtra (Emmerick 1970), the Suvarṇabhāsottamasūtra,40 and the Vimalakīrtinirdeśa (Skjærvø 1986, 229–60). Six out of the seven Khotanese texts were translated from Sanskrit Vorlagen, with the sole exception of the Bhaiṣajyagurusūtra, the sūtra of the Healing Buddha, which is proven to have a certain affinity to the fifth-century Chinese version (T.1331)41 and thus is probably of non-Indian provenance (Loukota 2019, 67–90). Apparently, the Khotanese reception of Mahāyāna literature, especially at its incipient stage, was by no means a one-way street, and India was not the only source of authority.

That being said, the lion’s share of Mahāyāna sūtras circulating in fifth- and sixth-century Khotan was Sanskrit (or Middle Indic) in origin. There was thus a gap between the language of the authoritative texts and that of the faith community, which was eastern Middle Iranian in speech. As long as members of the community were aware of the gap, the regulatory mechanisms controlling the translation of those texts became essential. This raises the question, above all, of whether the Buddha’s Word, in its ideal form, should be translated at all. Oskar von Hinüber (2014, 147–48) has pointed out an intriguing phenomenon that some Mahāyāna sūtras of the utmost importance, e.g. the Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra (viz. the Lotus Sūtra), seem to have never been translated into Khotanese. While this curiosity still remains to be fully accounted for in religio-historical perspective, it points to a defining feature of a conservative stratum of the local Buddhist community, namely, the overarching emphasis on ‘looking after the words’ (Textpflege) as the foremost “custodian of the tradition,”42 which takes priority over ‘looking after the meaning’ (Sinnpflege). In a Khotanese context, the priority of the former finds expression in the reluctance, if not deliberate refusal, to translate a text so as to maintain its original form in Sanskrit, a language that was incomprehensible to everybody in Khotan except educated monks.

The institution of looking after the words marks the first step towards canonization, according to Aleida and Jan Assmann (1987). Texts, which become fixed in wording, are thereby not only made taboo and ritualized,43 but also displaced and increasingly distanced from everyday life. The words are consecrated at the expense of the meaning. This process is thus to be complemented by expertise in the exegetic and applicative interpretations, lest the decay of the meaning (Sinnverfall) be inevitable. That is the reason for the rise of the expert-interpreter, the specialist in looking after the meaning (Assmann and Assmann 1987, 12–13). The Assmanns’ theory holds mutatis mutandis for the Khotanese institution of looking after the words by way of non-translation: The Buddha’s Word, in its Indic form, was foreign to many Khotanese Buddhists,44 who were speaking in tongues in the ritualized recitation. This was deemed a problem as well as an opportunity by a man of letters, whose chef-d’œuvre is hailed as a milestone in the history of Khotanese literature.

A Book to Remember

That milestone is the so-called Book of Zambasta. It is a voluminous, metrical compendium on various aspects of Mahāyāna Buddhism, consisting of twenty-four cantos in total. The vast majority of this book has come down to us in an almost complete main manuscript (St. Petersburg, SI P 6) which can be dated to the seventh or eighth century on paleographic grounds. The original title of this book is unfortunately lost to history, while Zambasta is but the name of a magistrate (pharṣavata)45 in the kingdom of Khotan, who, together with his son and family, commissioned the book. The floruit of the magistrate named Zambasta is unknown, but the Book of Zambasta must have circulated in the Tarim Basin at least two centuries before the production of the main manuscript, as a fragment (Berlin, T III Š 16) written in Early Turkestan Brāhmī (fifth/sixth century) has been identified as part of this book.46 The Book of Zambasta, therefore, was probably in the making during the fourth and fifth centuries, i.e., the aforesaid ‘Dark Ages’ of Khotanese history.

As for the man47 who brought the Book of Zambasta into being, no biography is forthcoming. The poet was probably well-read in Mahāyāna literature, since some cantos of the book are adapted from Mahāyāna sūtras, such as the Bhadramāyākaravyākaraṇa (canto 2; Régamey 1938, 5–6), the *Maitrībhāvanāprakaraṇa (canto 3; Duan 2007, 39–58), and the *Tathāgatapratibimbapratiṣṭhānuśaṃsā (canto 23),48 while sourced quotations from other Mahāyāna sūtras are found throughout the book.49 He was also familiar with certain established clusters of Mahāyāna sūtras, such as the Buddhāvataṃsaka and the Mahāsaṃnipāta, which seem to have gained currency in Khotan at that time (Emmerick 1968, 187). Despite his erudition, the poet seems to have had a somewhat different idea of what he was doing. By modern standards, this book was an indigenous Khotanese composition; but nowhere did the man speak of his own contribution as authorial. Instead, he used such verbs as ‘to translate,’ ‘to recite,’ and ‘to extract’ wherever reference is made to the activity he performed.50

However the verbs are to be construed, on no account would the poet have put in a claim to authorship, which would have been tantamount to taking the credit due to Buddhas. He rather considered himself something of a messenger conveying the Buddha’s Word to his fellow countrymen, whose mindset towards authoritative texts he trenchantly critiqued:

The Khotanese do not value the Dharma at all in Khotanese. They understand it badly in the Indian language. In Khotanese it does not seem to them to be the Dharma. For the Chinese the Dharma is in Chinese – in the Kashmirian language [the Dharma] is such [as] the Kashmirian sweetened wine51 – but they so learn it (i.e., in Chinese) that they also understand the meaning of it. To the Khotanese that seems to be the Dharma whose meaning they do not understand at all. When they hear it together with the meaning, it seems to them thus a different Dharma. (verses 23.4–6; Emmerick 1968, 343, 345, with modifications)

This oft-quoted passage is no doubt by far the most celebrated part of the Book of Zambasta. It has long been disputed what language “Kashmirian” was and whether the differentiation between “Indian” and “Kashmirian” was historical.52 But the purport of this passage has not been sufficiently explicated in its own right, and becomes clearer only if one takes into account the immediately following verses, which are often omitted from quotations:

Even an ordinary being would not utter a speech which has no meaning. How much less would the all-knowing Buddha be likely to utter meaningless words! In words the essential thing is the meaning. The meaning is indeed so much the essential thing that you should look on it in such a way that the Dharma is preached with that meaning. […] The meaning being unperceived, no one would escape from woes in saṃsāra. (verses 23.7–8, 11; Emmerick 1968, 345)

Apparently, the main point is that the Buddha did not utter meaningless words, and that a proper understanding of the Dharma’s meaning is prerequisite for its soteriological efficacy. The poet thus addressed not so much an issue of church language53 as of the priority of looking after the words, which is part and parcel of a seminal mindset traceable to a possibly pre-fourth-century Buddhist milieu in Khotan. In that milieu, attempts were made to canonize and perpetuate authoritative texts of Indian origin primarily by precluding Khotanese Buddhists from translating the texts into their own language. By that means, religious authority was monopolized by itinerant monks who brought along Indic texts and by ritual specialists who gained exclusive access to this sacrosanct body of literature.

The Buddha never spoke Khotanese, to be sure. But it is one thing to cherish Indian texts as valued sources of Buddhist teachings, and quite another to isolate the Buddha’s Word from the rest of the Khotanese-speaking world, illiterate in the Indian language. This conservative mindset, as is argued above, would naturally result in the decay of the meaning and, what is worse, a lingering loss of vitality in the roles played by those texts in the everyday life of ordinary Buddhists. These repercussions loom especially large in such a milieu as fourth- and fifth-century Khotan, where the rise of residential monasteries prepared the ground for a more durable locus of the interactions between clergy and laity. The poet of the Book of Zambasta thus responded, as it were, to the call of the Zeitgeist with alacrity. By restoring the centrality of the institution of looking after the meaning, he vindicated his decision to preach the Dharma in Khotanese not as expedient means, but as the sole approach that holds out the prospects of reenacting the Dharma’s soteriological efficacy in such a ‘borderland’ as Khotan, which was overshadowed by the perfection of the Indian ideal.54 This extraordinary man thus took on the herculean task of making Buddhas speak to his fellow countrymen, and his ambitious undertaking, as is evinced in the long-lasting impacts55 of the Book of Zambasta, was crowned with great success.

Tradent: Words and Deeds56

As is mentioned above, nowhere did the poet himself claim to be the ‘author’ of the Book of Zambasta, some cantos of which he allegedly ‘translated,’ ‘recited,’ or ‘extracted’ from scriptural sources. All the three verbs should be taken cum grano salis. For instance, canto 2, which he claimed to have ‘translated,’ is, by modern standards, no translation at all but a recasting, if not a recomposition from scratch (Régamey 1938, 5–6). Hence each of the three concepts (i.e., ‘translator,’ ‘bard,’ and ‘epitomist’) at best captures one of the multiple and intertwined dimensions of what it meant for him to produce this magnum opus, but none of them do full justice to his self-identity. Admittedly, any attempt at encapsulating the poet’s multifaceted activity in a single term is nothing short of curtailing him on a Procrustean bed. Despite its potential risks, such an attempt can be made on an ad hoc basis, as long as it identifies an apt substitute for ‘author’ such that offers an increased potential for comparative analysis. To my mind, a candidate for the term of that character is ‘tradent.’

The term ‘tradent’ has long been used in the study of Jewish rabbinic literature to highlight the ways in which rabbinic sages themselves understand their role in the making of this body of materials. As the de facto creators of rabbinic literature, they deny any creative role (and any innovative intent) in their own efforts, but only take responsibility for “preserving the integrity of the received version as received from an authoritative teacher” (Jaffee 2007, 22). In other words, the tradent, while producing the text, claims not to accomplish any work of originality but merely to pass on ancient teachings. Robert Mayer (2015), to the best of my knowledge, makes the first attempt at adopting this term into the field of Buddhist Studies.57 His intention is to shed new light on the idiosyncratic role played by Treasure revealers (gter ston) in the formation of Tibetan Treasure literature (gter ma). The Tibetan tradents share such conservative concerns of rabbinic sages as “they safely co[rral] individualistic flourishes within the safe bounds of the stock repertoire of established and accepted ritual modules” (Mayer 2015, 233). Although the genre of literature discussed by Mayer differs from the Book of Zambasta in significant aspects, they have at least one characteristic in common, namely that their genesis cannot be adequately accounted for through the assumption of an author of originality.

Sten Konow was struck by an ostensible lack of originality in the Book of Zambasta, which he attributed to “a learned collector [but] not an original poet” (Konow 1939, 32). A principal factor in this impression is the poet’s reluctance to claim any authorial credit for himself, as is mentioned above. He sought to be seen as a conservative tradent faithful to the tradition, and as such he gave voice to his apprehensions about possible mistakes that he could have committed in performing his duties as a tradent:

Since I have translated this teaching, however extremely small [and] poor my knowledge, I seek pardon from all the divine Buddhas, for whatever meaning I have spoiled here. (verse 1.189; Emmerick 1968, 9; modified after Maggi 2009a, 157)

Whatever there may be here which the Buddha has not spoken in a sūtra one should not accept. That is all my fault. (verse 8.48; Emmerick 1968, 141)

First-person statements of this kind, at first glance, appear to resemble the usual disclaimers in scholarly publications. It is customary for scholars to include, in acknowledgments of their publications, statements to the effect that all remaining mistakes are their own. If the parallelism could be taken for granted, it would follow that the poet of the Book of Zambasta, like every scholar, made every effort to steer clear of mistakes, and that despite his best efforts, he was aware of the existence of possible, undetected mistakes which could be pointed out by a learned reading public.58 It remains to be examined whether this is the case.

The mistakes, as is quoted above, are basically twofold: subtraction and addition. The former consists of misrepresentations of Buddhist teachings whose meaning is thereby (partially) lost in ‘translation,’ while the latter results in the contamination of scriptural sources with non-scriptural ones. Both concern meaning rather than the words, in accord with the aforementioned emphasis on the primacy of looking after the meaning, which the poet vehemently championed. The statements thus presuppose the semantic integrity of a closed canon of the Mahāyāna, from which nothing should be taken away and to which nothing should be added. This presupposition is reminiscent of the famous canon formula (e.g. in Deuteronomy 13.1: “The entire word that I command you shall you take care to perform; you must neither add to it nor take away from it!”), which is deeply rooted in the Biblical and Greek traditions.59 But in the Buddhist world, there is no precedent for the statements in the Book of Zambasta, while a closed and fixed Buddhist canon was not entrenched elsewhere than in Sri Lanka before the fifth century CE (Collins 1990, 89–126).

It is not clear whether the Khotanese poet penned the lines by way of off-the-cuff remarks or drew inspiration from a trope that originated in other traditions. Nor is there any definitive evidence for a Khotanese canon of Mahāyāna sūtras, whether closed or not, before the emergence of the Book of Zambasta. The idea of the totality of Mahāyāna sūtras as valued objects of cultic reverence seems to have been gaining ground in *Cugopa(n),60 a petty kingdom to the west of Khotan (present-day Karghalik), no later than the second half of the sixth century.61 It seems conceivable that the aspiration towards the demarcation, if not the closure, of a Mahāyāna canon, something which never occurred in India, had been in gestation for some time at the southwestern corner of the Tarim Basin, as the Khotanese poem saw the light of day. It may thus come as no surprise that the poet in Khotan conceived a similar idea.62 The contours of a Mahāyāna canon may be discernible in canto 6 of the Book of Zambasta, which, according to its introit (verse 6.1; Emmerick 1968, 117), contains fifty-nine verses, each from a different sūtra. If so, this canto would be a florilegium of Mahāyāna sūtras, which, as Mauro Maggi argues, constituted a Mahāyāna “canon of fifty-nine texts as recognized in Khotan” at that time (2009b, 347).

The claim in the introit is partially borne out by the recent identification of the sources of twenty-odd verses in this canto (R. Chen and Loukota 2018). Although a good half of the canto still remains unsourced, so far nothing speaks against the assumption that the poet did live up to his words by making precisely a verse out of each sūtra. If the fifty-nine Mahāyāna sūtras add up to something of a canon, they provide an advantageous lens through which to appraise the extent to which the poet delivered on his purported commitments as a tradent. Due to the limited space of this essay, we will content ourselves here with looking into a single verse, i.e. verse 6.12, being a quotation from the Tathāgataguhya(ka), a Mahāyāna sūtra which was first translated into Chinese in the late third century. The verse in question appears to be an abridgement of a lesser-known simile, in which Jīvaka, the king of physicians, is mentioned:63

With herbs has Jīvaka prepared and adorned a girl, [thereby he] removes the diseases [of the world]. Just so does the Buddha through the body of dharmas [remove] all afflictions (kleśa) without effort. (R. Chen and Loukota 2018, 161)

A Sanskrit version of the same simile was quoted in its entirety by the seventh-/eighth-century Buddhist scholastic Śāntideva in the Śikṣāsamuccaya, an anthology containing numerous quotations from a variety of Mahāyāna sūtras. In that context, the simile, taught by Vajrapāṇi to Śāntamati, reads as follows:64

Just as, Śāntamati, when the king of physicians Jīvaka collected all medicine, he made the form of a girl (composed of) a collection of medicinal herbs, which is agreeable, good-looking, well-made, well-completed, and well-prepared. She was going to and fro, standing, sitting down, and sleeping, without thinking or imagination. Thither came sick dignitaries: kings, vicegerents, guild-leaders, bankers, courtiers, and petty rulers. Jīvaka let them unite with the medicine-girl. Immediately after the union that they consummated, all their diseases were appeased, and they became free from illness, sound, and unimpaired. […] Just so, Śāntamati, is the Bodhisattva (i.e., the Buddha) essentially characterized by the body of dharmas. Whatever sentient beings – women, men, boys, girls – distressed by passion, hatred, and delusion, touch his body, all their afflictions (kleśa) are soothed as soon as they touch it, and they feel (their) body free from distress. (R. Chen and Loukota 2018, 162–63, with modifications)

Compared with the Sanskrit version, the Khotanese verse is so laconic that one can hardly make sense of it without looking up the original narrative context. It lays bare the unsettling fact that the tradent did take things away. That is to say, he condensed a meandering narrative into a verse of four lines, and, in doing so, reduced the source information to its skeleton. In consequence, the meaning was often veiled, if not entirely spoiled.

On the other hand, things are added to the simile, as is evinced by the phrase ‘without effort’ (anābhoga), which finds no counterpart in any other version of this sūtra. This phrase is probably an innovation by the tradent, who interpreted the Buddha’s salvific use of his body of dharmas as ‘effortless.’ This interpretation is in line with a seminal idea that all activities of the Buddha or a spiritually advanced Bodhisattva are carried out spontaneously, without volitional effort, for any practitioner from the eighth stage of the Bodhisattva path onwards abides in an impassive state devoid of superficial appearances.65 Judging from this example, it seems suspect whether the tradent ever made efforts to refrain from ‘subtraction’ and ‘addition,’ as one may suppose; and even if he did, his efforts did not bear fruit to any significant degree. Nolens volens he made tremendous contributions to the diversity of the textual tradition of the Mahāyāna, keeping an eye not only on metrical constraints, but also on the latest scholastic trends. He seems to have had no guilty conscience at all about weaving together ideas of different provenances.

These observations invite us to reconsider the aforesaid statements in rhetorical and pragmatic terms. A word-for-word rendition of the original was apparently not what the tradent actually aspired to. He owned up to his “faults” and pleaded with Buddha for leniency; but there is no indication whatsoever that he strove to steer clear of such “faults,” which occur on nearly every page of the Book of Zambasta. Therefore, to read those statements simply as a plea of mea culpa is to miss the point. The tradent was different from the scholar who adds the usual disclaimers to a publication before it goes to the learned reader, insofar as the target audience of the Book of Zambasta consisted of Khotanese believers who understood the Dharma “badly in the Indian language” (verse 23.4; Emmerick 1968, 343). They were not quite capable of reading Indic Buddhist texts, much less comparing the Khotanese poem with its (mostly unspecified) Indian sources. In this regard, the supposed concern about the ambiguity of responsibility for potential mistakes seems to have been at least excessive, and thus is unlikely to have motivated the tradent to add those statements.

The quest for the function of those statements entails a better understanding of the tradent’s role in the transmission process. By dint of those statements, the tradent was not primarily aimed at confessing his own “faults,” or admonishing others against such “faults.” His objective was, to my mind, rather to inculcate a sense of reverence and awe for Mahāyāna sūtras in Khotanese believers by underscoring the sacredness and integrity of this body of literature as the Buddha’s Word, which must therefore remain intact. It is beyond the shadow of a doubt that the tradent ran rings around his countrymen in terms of textual expertise. Both the sermon, to which the Book of Zambasta was probably tailored,66 and the authority derived from this missionary role were precisely based on the tradent’s power to control the process of conveying the meaning of the Buddha’s Word to the Khotanese. Hence it is also plausible to read those statements as an emphatic asseveration of his mastery over this body of literature rather than a token of his ostensible concern about mistranslation etc.67 A special role was accorded to the tradent in his capacity as expert-interpreter, who was thus entitled to change, update, and harmonize the sūtras according to certain criteria. On a par with those sūtras, his exegesis was canonized.

Concluding Remarks

History is more complex than what chance finds reveal. Khotanese Buddhists were not the homines unius libri (‘men of one book’), and neither was the Book of Zambasta their bible. It would be a methodological hazard to plumb the ethos of a particular era through a sole book, however informative it could be. Hence one must bear in mind the sampling nature of the present research, which at best represents a limited view of what actually happened in Khotan during the fourth and fifth centuries CE. Incomplete as it may be, the limited view does spotlight a deep-seated transformation of the structure and the source of authority in the local Buddhist milieu, which was caught in a transition from a ritual-oriented priesthood based on long-distance transmission to a text-centered monasticism under the supremacy of the Mahāyāna. If the Book of Zambasta is anything to go by, an essential aspect of this transformation was the canonization of Mahāyāna sūtras with special emphasis on the principle of looking after the meaning rather than the words, despite the high esteem in which the latter had been held theretofore. The closure of a Mahāyāna canon is likely to have taken place at least on the ideological level, setting in motion a paradoxical process: While exclusive sacredness was awarded to the sūtras, the focus was shifted to their interpretation, and authority was removed from the text-bearer and bestowed on the expert-interpreter, i.e., the tradent, whose exegesis was accorded quasi-canonical status and carried weight with Khotanese believers. Authority was thus redistributed.

The historical factors that triggered this transformation remain nebulous for the most part. The influence of the Chinese model is not impossible, but its likelihood is not to be overestimated either, inasmuch as Khotanese monks were confronted with different problems from their brethren in China. In addition, it merits special note that the kingdom of Khotan was forced to cut loose from its suzerain in northern China during the period in question, partly due to the aforementioned desertion of Caḍ̱ota and Kroraina. By the mid-fifth century, Chinese military power was no longer in a position to effectively shelter vassal states on the Silk Routes from external assaults68 at a moment when the territorial expansion of the Avars (aka. Rouran, Ruanruan)69 and the Hephthalites ushered in a reshuffle of regional power.70 In the aftermath of the warfare against the Hephthalites (484–534), Hans Bakker observed “the dissolution of the Gupta empire and the rise of autonomous, regional states in northern India” (2017, 24). It is thus not unlikely that the disintegration of the Sino-centric tributary system in the Tarim Basin a few decades earlier would have compelled oasis states overshadowed by the Avars and later also by the Hephthalites, such as Khotan and *Cugopa(n), to seek autonomy while their diplomats were tactfully mediating between the powers to maintain a fragile independence (Rong 2018, 74–75). Against this historical background, it is possible to hypothesize that the ruling élite in Khotan or *Cugopa(n) readily shifted to the Mahāyāna and ardently endorsed the clerical pursuit of canon and authority in order to unite the people of the country, particularly at a time of political upheaval, under a localized identity of Mahāyāna Buddhism, a religion which distinguished themselves from not merely their near neighbors in the Tarim Basin (e.g. Kucha) but also their nomadic rivals. Admittedly, this hypothesis is speculative; but it might not be useless here to present a working hypothesis that will be tested and refined in case further evidence comes to light.

References

Acharya, Diwakar. 2010. “Evidence for Mahāyāna Buddhism and Sukhāvatī Cult in India in the Middle Period: Early Fifth to Late Sixth Century Nepalese Inscriptions.” Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 31 (1–2): 23–75.

Allon, Mark, and Richard Salomon. 2010. “New Evidence for Mahāyāna in Early Gandhāra.” The Eastern Buddhist 41 (1): 1–22.

Assmann, Aleida, and Jan Assmann. 1987. “Kanon und Zensur.” In Kanon und Zensur, edited by A. Assmann and J. Assmann, 7–27. Munich: Fink.

Assmann, Jan. 2011. Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Atwood, Christopher. 1991. “Life in Third–Fourth Century Cadh’ota: A Survey of Information Gathered from the Prakrit Documents Found North of Minfeng (Niya).” Central Asiatic Journal 35: 161–99.

Bailey, Harold W. 1951. “The Staël-Holstein Miscellany.” Asia Major, New Series 2 (1): 1–45.

———. 1967. Prolexis to the Book of Zambasta: Khotanese Texts VI. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bakker, Hans. 2017. Monuments of Hope, Gloom, and Glory: In the Age of the Hunnic Wars, 50 Years That Changed India (484–534). Amsterdam: Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Bendall, Cecil. 1897–1912. Çikshāsamuccaya: A Compendium of Buddhistic Teaching Compied by Çāntideva Chiefly from Earlier Mahāyāna-Sūtras. St. Petersburg: Académie Impériale des Sciences.

Boyce, Mary. 1975. A History of Zoroastrianism. Volume One: The Early Period. Leiden: Brill.

Brough, John. 1965. “Comments on Third-Century Shan-Shan and the History of Buddhism.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 28 (3): 582–612.

Burrow, Thomas. 1940. A Translation of the Kharoṣṭhī Documents from Chinese Turkestan. London: The Royal Asiatic Society.

Cabezón, José I. 1992. “Vasubandhu’s Vyākhyāyukti on the Authenticity of the Mahāyāna Sūtras.” In Texts in Context: Traditional Hermeneutics in South Asia, edited by J. R. Timm, 221–43. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Campany, Robert F. 2012. Signs from the Unseen Realm: Buddhist Miracle Tales from Early Medieval China. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Canevascini, Giotto. 1993. The Khotanese Saṅghāṭasūtra. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag.

Chavannes, Édouard. 1905. “Jinagupta (528–605 après J.-C.).” T’oung Pao, Second Series 6 (3): 332–56.

Chen, Jinhua. 2017. “The Borderland Complex and the Construction of Sacred Sites and Lineages in East Asian Buddhism.” In Buddhist Transformations and Interactions: Essays in Honor of Antonino Forte, edited by V. H. Mair, 65–106. Amherst: Cambria.

Chen, Ruixuan. 2018. “The Nandimitrāvadāna: A Living Text from the Buddhist Tradition.” PhD Dissertation, Leiden University.

Chen, Ruixuan, and Diego Loukota. 2018. “Mahāyāna Sūtras in Khotan: Quotations in Chapter 6 of the Book of Zambasta (I).” Indo-Iranian Journal 61 (2): 131–75.

Chen, Zhiyuan. 2018. “Banre jing zaoqi chuanbo shishi bianzheng.” Sui Tang Liao Song Jin Yuan shi luncong 8: 99–116.

Collins, Steven. 1990. “On the Very Idea of the Pali Canon.” Journal of the Pali Text Society 15: 89–126.

Colpe, Carsten. 1987. “Sakralisierung von Texten und Filiationen von Kanons.” In Kanon und Zensur, edited by A. Assmann and J. Assmann, 80–92. Munich: Fink.

Deeg, Max. 2005. Das Gaoseng-Faxian-Zhuan als religionsgeschichtliche Quelle: Der älteste Bericht eines chinesischen buddhistischen Pilgermönchs über seine Reise nach Indien mit Übersetzung des Textes. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

———. 2006. “Unwirkliche Gegner: Chinesische Polemik gegen den Hīnayāna-Buddhismus.” In Jaina-Itihāsa-Ratna: Festschrift für Gustav Roth zum 90. Geburtstag, edited by U. Hüsken, Petra Kieffer-Pülz, and Anne Peters, 103–25. Marburg: Indica et Tibetica.

Deeg, Max, Oliver Freiberger, and Christoph Kleine. 2011. Kanonisierung und Kanonbildung in der asiatischen Religionsgeschichte. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Drewes, David. 2010. “Early Indian Mahāyāna Buddhism I: Recent Scholarship, II: New Perspectives.” Religion Compass 4 (2): 55–65, 66–74.

Duan, Qing. 2007. “The Maitrī-Bhāvanā-Prakaraṇa: A Chinese Parallel to the Third Chapter of the Book of Zambasta.” In Iranian Languages and Texts from Iran and Turan: Ronald E. Emmerick Memorial Volume, edited by M. Macuch, Mauro Maggi, and Werner Sundermann, 44–58. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Duby, Georges. 1975. “Histoire-société-imaginaire.” Dialectiques 10/11: 111–23.

Edgerton, Franklin. 1953. Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit Dictionary. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Emmerick, Ronald E. 1967. Tibetan Texts Concerning Khotan. London: Oxford University Press.

———. 1968. The Book of Zambasta: A Khotanese Poem on Buddhism. London: Oxford University Press.

———. 1970. The Khotanese Śūraṅgamasamādhisūtra. London: Oxford University Press.

———. 1997. Studies in the Vocabulary of Khotanese III. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Falk, Harry, and Seishi Karashima. 2012. “A First-Century Prajñāpāramitā Manuscript from Gandhāra: Parivarta 1.” Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University 15: 19–61.

———. 2013. “A First-Century Prajñāpāramitā Manuscript from Gandhāra: Parivarta 5.” Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University 16: 97–169.

Fang, Guangchang. 2014. “Yaoshifo tanyuan: Dui Yaoshifo hanyi fodian de wenxianxue kaocha.” Zongjiaoxue yanjiu 4: 90–100.

Filippone, Ela. 2007. “Is the Judge a Questioning Man? Notes in the Margin of Khotanese Pharṣavata-.” In Iranian Languages and Texts from Iran and Turan: Ronald E. Emmerick Memorial Volume, edited by M. Macuch, Mauro Maggi, and Werner Sundermann, 75–86. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Folkert, Kendall W. 1989. “The ‘Canons’ of ‘Scripture’.” In Rethinking Scripture: Essays from a Comparative Perspective, edited by M. Levering, 170–79. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Forte, Antonino. 1985. “Hui-chih (fl. 676–703 A.D.), A Brahmin Born in China.” Estratto da Annali dell’Instituto Universitario Orientale 45: 106–34.

Giles, Herbert Allen. 1923. The Travels of Fa-Hsien (399–414 A.D.), or Record of the Buddhistic Kingdoms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Golden, Peter. 2013. “Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran.” In The Steppe Lands and the World Beyond Them: Studies in Honor of Victor Spinei on His 70th Birthday, edited by F. Curta and B.-P. Maleon, 43–66. Jassy: Editura Universitatii “Alexandru Ioan Cuza”.

Goodman, Charles. 2016. The Training Anthology of Śāntideva: A Translation of the Śikṣā-Samuccaya. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grenet, Franz. 2002. “Regional Interaction in Central Asia and Northwestern India in the Kidarite and Hephthalite Periods.” In Indo-Iranian Languages and Peoples, edited by N. Sims-Williams, 203–24. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Halbertal, Moshe. 1997. People of the Book: Canon, Meaning, and Authority. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hansen, Valerie. 2004. “Religious Life in a Silk Road Community: Niya During the Third and Fourth Centuries.” In Religion and Chinese Society. Volume One: Ancient and Medieval China, edited by John Lagerwey, 279–315. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press.

———. 2012. The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harrison, Paul. 1987. “Who Gets to Ride in the Great Vehicle? Self-Image and Identity Among the Followers of the Early Mahāyāna.” Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 10 (1): 67–89.

———. 1993. “The Earliest Chinese Translations of Mahāyāna Buddhist Sūtras: Some Notes on the Works of Lokakṣema.” Buddhist Studies Review 10 (2): 135–77.

———. 1995. “Searching for the Origins of the Mahāyāna: What Are We Looking for?” The Eastern Buddhist 28 (1): 48–69.

———. 2018. “Lokakṣema.” In Brill’s Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Volume Two: Lives, edited by J. A. Silk, Vincent Eltschinger, Richard Bowring, and Micheal Radich, 700–706. Leiden: Brill.

Hartmann, Jens-Uwe. 2019. “The Earliest ‘Mahāyāna’ Sūtra Manuscripts and What They Tell Us.” Hōrin 20: 13–22.

Hayashiya, Tomojirō. 1941. Kyōroku kenkyū: zenpen. Tōkyō: Iwanami shoten.

Herrin, Judith. 2009. “Book Burning as Purification.” In Transformations of Late Antiquity: Essays for Peter Brown, edited by P. Rousseau and M. Papoytsakis, 205–22. Farnham: Ashgate.

Hinüber, Oskar von. 2014. “A Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra Manuscript from Khotan: The Gift of a Pious Khotanese Family.” Journal of Oriental Studies 24: 134–56.

Inokuchi, Taijun. 1961. “Tokara go oyobi Uten go no butten.” In Seiiki bunka kenkyū. Daishi: Chūō Ajia kodai go bunken, edited by Seiiki bunka kenkyūkai, 317–288. Monumenta Serindica 4. Kyoto: Hōzōkan.

Jaffee, Martin S. 2007. “Rabbinic Authorship as a Collective Enterprise.” In The Cambridge Companion to the Talmud and Rabbinic Literature, edited by C. E. Fonrobert and M. S. Jaffee, 17–37. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kondō, Ryūkō. 1936. Daśabhūmīśvara nāma Mahāyānasūtraṃ. Tōkyō: Daijō bukkyō kenyōkai.

Konow, Sten. 1939. “The Late Professor Leumann’s Edition of a New Saka Text II.” Norsk Tidsskrift for Sprogvidenskap 11: 5–84.

Kumamoto, Hiroshi. 1982. “Khotanese Official Documents in the 10th Century A.D.” PhD Dissertation, University of Pennsylvania.

Leumann, Ernst. 1933–1936. Das nordarische (sakische) Lehrgedicht des Buddhismus: Text und Übersetzung. Leipzig: Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft.

Levinson, Bernard M. 2009. “The Neo-Assyrian Origins of the Canon Formula in Deuteronomy 13:1.” In Scriptural Exegesis: The Shapes of Culture and the Religious Imagination. Essays in Honour of Michael Fishbane, edited by D. A. Green and L. S. Lieber, 25–45. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lévi, Sylvain. 1907. Mahāyāna-Sūtrālaṃkāra: Exposé de la doctrine du Grand Véhicule selon le système Yogācāra. Paris: Librairie Honoré Champion.

———. 1908. “Les saintes écritures du Bouddhisme: Comment s’est constitué le canon sacré.” Annales du Musée Guimet: Bibliothèque du vulgarisation 31 (September): 105–29.

Loewe, Michael. 1969. “Chinese Relations with Central Asia, 260–90.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 32 (1): 91–103.

Loukota, Diego. 2014. “The Anantamukhanirhāradhāraṇī: A Critical Evaluation of New Textual Material.” MA Thesis, Peking University.

———. 2019. “Made in China? Sourcing the Old Khotanese Bhaiṣajyaguruvaiḍūryaprabhasūtra.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 139 (1): 67–90.

———. 2020. “A New Kharoṣṭhī Document from Kucha in the Hetian County Museum Collection.” In Non-Han Literature Along the Silk Road, edited by X. Li, 91–113. Singapore: Springer.

MacCormack, Geoffrey. 1995. “Was the Ordeal Known in Ancient China?” Revue Internationale Des Droits de L’antiquité 42: 71–93.

Maggi, Mauro. 2004. “The Manuscript T III Š 16: Its Importance for the History of Khotanese Literature.” In Turfan Revisited: The First Century of Research into the Arts and Cultures of the Silk Road, edited by D. Durkin-Meisterernst, Simone-Christiane Raschmann, Jens Wilkens, Marianne Yaldiz, and Peter Zieme, 184–90. Berlin: Reimer.

———. 2009a. “Annotations on the Book of Zambasta, I.” In Literarische Stoffe und ihre Gestaltung in mitteliranischer Zeit: Kolloquium anlässlich des 70. Geburtstages von Werner Sundermann, edited by D. Durkin-Meisterernst, 153–71. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag.

———. 2009b. “Khotanese Literature.” In The Literature of Pre-Islamic Iran, edited by R. E. Emmerick and M. Macuch, 330–417. New York: Tauris.

———. 2015. “A Folio of the Ratnakūṭa (Kāśyapaparivarta) in Khotanese.” Dharma Drum Journal of Buddhist Studies 17: 101–43.

Makinson, D. C. 1965. “The Paradox of the Preface.” Analysis 25 (6): 205–7.

Martini, Giuliana. 2011. “A Large Question in a Small Place: The Transmission of the Ratnakūṭa (Kāśyapaparivarta) in Khotan.” Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University 14: 135–83.

———. 2013. “Bodhisattva Texts, Ideologies and Rituals in Khotan in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries.” In Buddhism Among the Iranian Peoples of Central Asia, edited by M. Maggi, Matteo De Chiara, and Giuliana Martini, 13–69. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

———. 2014a. “‘Mahāratnakūṭa’ Scriptures in Khotan: A Quotation from the Samantamukhaparivarta in the Book of Zambasta.” Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University 17: 337–47.

———. 2014b. “Transmission of the Dharma and Reception of the Text: Oral and Aural Features of the Fifth Chapter of the Book of Zambasta.” In Buddhism Across Asia: Networks of Material, Intellectual and Cultural Exchange, edited by T. Sen, 131–69. Manohar: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies Singapore.

Mayer, Alexander Leonhard. 1990. “Die Gründungslegende Khotans.” In Buddhistische Erzähl-literatur und Hagiographie in türkischer Überlieferung, edited by J. P. Laut and K. Röhrborn, 37–65. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Mayer, Robert. 2015. “gTer Ston and Tradent: Innovation and Conservation in Tibetan Treasure Literature.” Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 36/37 (1-2): 227–42.

McDermott, James P. 1984. “Scripture as the Word of the Buddha.” Numen-International Review for the History of Religions 31 (1): 22–39.

Mitra, Rajendralal. 1888. Ashṭasáhasriká: A Collection of Discourses on the Metaphysics of the Maháyána School of the Buddhists. Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press.

Nattier, Jan. 1990. “Church Language and Vernacular Language in Central Asian Buddhism.” Numen-International Review for the History of Religions 37: 195–217.

———. 2003. A Few Good Men: The Bodhisattva Path According to the Inquiry of Ugra (Ugraparipr̥cchā). Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Neelis, Jason. 2011. Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange Within and Beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia. Leiden: Brill.

Norman, K. R. 1997. A Philological Approach to Buddhism: The Bukkyō Dendō Kyōkai Lectures 1994. London: School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

Oeming, Manfred. 2013. “‘Du sollst nichts hinzufügen und nichts wegnehmen’ (Dtn 13,1): Altorientalische Ursprünge und biblische Funktionen der sogenannten Kanonformel.” In Verstehen und Glauben: Exegetische Bausteine zu einer Theologie des Alten Testaments, 121–37. Vienna: Philo.

Panaino, Antonio. 2015. “Ὁμόγλωττοι παρὰ μικρόν?” Electrum 22: 87–106.

Pelliot, Paul. 1963. Notes on Marco Polo II. Paris: Adrien-Maisonneuve.

Rahder, Johannes. 1926. Daśabhūmikasūtra et Bodhisattvabhūmi, Chapitres Vihāra et Bhūmi. Paris: Paul Geuthner.

Régamey, Konstanty. 1938. The Bhadramāyākāravyākaraṇa: Introduction, Tibetan Text, Translation and Notes. Warsaw: Nakładem Towarzystwa Naukowego Warszawskiego.

Rong, Xinjiang. 2018. “The Rouran Qaghanate and the Western Regions During the Second Half of the Fifth Century Based on a Chinese Document Newly Found in Turfan.” In Great Journeys Across the Pamir Mountains: A Festschrift in Honor of Zhang Guangda on His Eighty-Fifth Birthday, edited by H. Chen and X. Rong, 59–82. Leiden: Brill.

Salomon, Richard. 1999. “A Stone Inscription in Central Asian Gāndhārī from Endere (Xinjiang).” Bulletin of the Asia Institute, New Series 13: 1–13.

———. 2002. “A Sanskrit Fragment Mentioning King Huviṣka as a Follower of the Mahāyāna.” In Buddhist Manuscripts in the Schøyen Collection II, edited by J. E. Braarvig, 255–67. Oslo: Hermes.

Sander, Lore. 2005. “Remarks on the Formal Brāhmī Script from the Southern Silk Route.” Bulletin of the Asia Institute, New Series 19: 133–44.

Sarefield, Daniel C. 2006. “Book-Burning in the Christian Roman Empire: Transforming a Pagan Rite of Purification.” In Violence in Late Antiquity: Perceptions and Practices, edited by H. A. Drake, 287–96. Farnham: Ashgate.

Schäublin, Christoph. 1974. “Μήτε προσθεῖναι μήτ᾽ ἀφελεῖν.” Museum Helveticum 31 (3): 144–49.

Schopen, Gregory. 1979. “Mahāyāna in Indian Inscriptions.” Indo-Iranian Journal 21: 1–19.

———. 2000. “The Mahāyāna and the Middle Period in Indian Buddhism: Through a Chinese Looking-Glass.” The Eastern Buddhist 32 (2): 1–25.

Sheppard, G. T. 1987. “Canon.” In The Encyclopedia of Religion. Volume Three, edited by M. Eliade, 62–69. New York: MacMillan.

Shimoda, Masahiro. 2009. “The State of Research on Mahāyāna Buddhism: The Mahāyāna as Seen in Developments in the Study of Mahāyāna Sūtras.” Acta Asiatica: Bulletin of the Institute of Eastern Culture 96: 1–23.

Silk, Jonathan A. 2002. “What, If Anything, Is Mahāyāna Buddhism? Problems of Definitions and Classifications.” Numen-International Review for the History of Religions 49 (4): 355–405.

———. 2015. “Canonicity.” In Brill’s Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Volume One: Literature and Languages, edited by J. A. Silk, Oskar von Hinüber, and Vincent Eltschinger, 5–37. Leiden: Brill.

Sinor, Denis. 1990. “The Establishment and Dissolution of the Türk Empire.” In The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, edited by D. Sinor, 285–316. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Skjærvø, Prods Oktor. 1986. “Khotanese Fragments of the Vimalakīrtinirdeśasūtra.” In Kalyāṇamitrārāgaṇam: Essays in Honour of Nils Simonsson, edited by E. Kahrs, 229–60. Oslo: Norwegian University Press.

———. 2003. “Fragments of the Ratnakūṭa-Sūtra (Kāśyapaparivarta) in Khotanese.” In Religious Themes and Texts of Pre-Islamic Iran and Central Asia: Studies in Honour of Professor Gherardo Gnoli on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday, edited by Carlo G. Cereti, Mauro Maggi, and Elio Provasi, 409–20. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag.

———. 2004. This Most Excellent Shine of Gold, King of Kings of Sutras: The Khotanese Suvarṇabhāsottamasūtra. Cambridge MA: The Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Harvard University.

———. 2012. “Khotan: An Early Center of Buddhism in Chinese Turkestan.” In Buddhism Across Boundaries: The Interplay of Indian, Chinese, and Central Asian Source Materials, edited by J. R. McRae and J. Nattier, 106–41. Sino-Platonic Papers 222. Philadelphia: The Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, University of Pennsylvania.

Strauch, Ingo. 2018. “Early Mahāyāna in Gandhāra: New Evidence from the Bajaur Mahāyāna Sūtra.” In Setting Out on the Great Way: Essays on Early Mahāyāna Buddhism, edited by Paul Harrison, 207–42. Sheffield: Equinox.

Strickmann, Michel. 1990. “The Consecration Sūtra: A Buddhist Book of Spells.” In Chinese Buddhist Apocrypha, edited by R. E. Buswell, 75–118. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Tafażżolī, Ahmed. 1983. “Ādurbād ī Mahrspandān.” Encyclopædia Iranica 1 (5): 477. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/adurbad-i-mahrspandan.

Thomas, F. W. 1924. “Notes Relating to Sir M.A. Stein’s Ancient Khotan.” Zeitschrift Für Buddhismus 6: 184–87.

———. 1925. “The Language of Ancient Khotan.” Asia Major 2: 215–71.

———. 1935. Tibetan Literary Texts and Documents Concerning Chinese Turkestan. Part One: Literary Texts. London: The Royal Asiatic Society.

Tremblay, Xavier. 2007. “The Spread of Buddhism in Serindia: Buddhism Among Iranians, Tocharians, and Turks Before the 13th Century.” In The Spread of Buddhism, edited by A. Heirman and S. P. Bumbacher, 75–129. Leiden: Brill.

Unnik, W. C. van. 1949. “De la règle μήτε προσθεῖναι μήτε ἀφελεῖν dans l’histoire du canon.” Vigiliae Christianae 3: 1–36.

Vaissière, Étienne de la. 2005. Sogdian Traders: A History. Leiden: Brill.

———. 2020. “The Origin of the Name Mongol.” In. https://www.academia.edu/s/c525d3ea12?%3Fsource=news.

Veltri, Giuseppe. 2002. “Tradent und Traditum im antiken Judentum: Zu einer sog. Kanonformel.” In Gegenwart der Tradition: Studien zur jüdischen Literatur und Kulturgeschichte, edited by Giuseppe Veltri, 3–22. Leiden: Brill.

Wen, Xin. 2008. “Yutian guo guanhao kao.” Dunhuang Tulufan yanjiu 11: 121–46.

———. 2016. “What’s in a Surname? Central Asian Participation in the Culture of Naming of Medieval China.” Tang Studies 34 (1): 73–98.

Wille, Klaus. 2014. “Survey of the Identified Sanskrit Manuscripts in the Hoernle, Stein, and Skrine Collections of the British Library (London).” In From Birch Bark to Digital Data: Recent Advances in Buddhist Manuscript Research, edited by P. Harrison and J.-U. Hartmann, 223–47. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Wogihara, Unrai. 1930–1936. Bodhisattvabhūmi: A Statement of Whole Course of the Bodhisattva (Being Fifteenth Section of Yogācārabhūmi). Tōkyō: Sankibō.

Wu, Xinhua. 2013. “Archaeological Discoveries in Domoko.” IDP News 41: 5.

Yamaguchi, Susumu. 1934. Madhyāntavibhāgaṭīkā: Exposition systèmatique du Yogācāravijñaptivāda. Nagoya: Librairie Hajinkaku.

Yamazaki, Gen’ichi. 1990. “The Legend of the Foundation of Khotan.” The Memoirs of the Tōyō Bunko 48: 55–80.

Zhang, Guangda, and Xinjiang Rong. 1993. Yutian shi congkao. Shanghai: Shanghai shudian.

Zhang, Xun. 1985. Faxian zhuan jiaozhu. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe.

Zürcher, Erik. 1990. “Han Buddhism and the Western Region.” In Thought and Law in Qin and Han China: Studies Dedicated to Anthony Hulsewé on the Occasion of His Eightieth Birthday, edited by W. L. Idema and E. Zürcher, 158–82. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

———. 2007. The Buddhist Conquest of China: The Spread and Adaptation of Buddhism in Early Medieval China. 3rd ed. Leiden: Brill.

The origin of this designation is obscure; see Collins (1990, 92–93).↩︎

For attempts at an overview of the formation of canon(s) and its various aspects in the history of Buddhism, see Lévi (1908), McDermott (1984), Norman (1997, 131–48), and Silk (2015). See also Deeg, Freiberger and Kleine (2011), especially the contributions by Salomon, Freiberger, Kleine, Deeg, Wilkens, and Kollmar-Paulenz.↩︎

See Sheppard (1987, 64–66). This typology is significantly different from a similar twofold typology of “canon” proposed by Folkert (1989, 173), which consists in the distinction between a ‘vectored’ (i.e., carried) canon, whose authoritative status is derived from its use by the faith community, and a ‘vectoring’ canon, which is prestigious due to the divinely revealed source and itself functions as a carrier of religious activity.↩︎

For “contra-present” as opposed to “foundational,” see Assmann (2011, 62–66).↩︎

A case in point is the Pāli canon, whose closure was conditioned by a strategy of legitimation by a specific sect of Mainstream Buddhism in Sri Lanka in the early centuries CE; see Collins (1990, 89–126).↩︎

For useful surveys of the long history of scholarship on the origin(s) of Mahāyāna Buddhism, see Shimoda (2009) and Drewes (2010). For the discovery of the so far oldest Mahāyāna texts in Gāndhārī (first to fourth centuries CE), whose significance for the study of early Mahāyāna Buddhism cannot be overestimated, see Allon and Salomon (2010, 1–22), Strauch (2018, 207–42), and most recently Hartmann (2019, 13–22).↩︎

That is to say, defining a class of objects by means of a set of features or characteristics shared by every member of the class. For a thorough critique of the instances of monothetic classification in the received definitions of Mahāyāna Buddhism, see Silk (2002, 355–405), who proposes the alternative method of polythetic classification that operates on the basis of a variable set of features or characteristics possessed by a large number of members, but not by every member of the class.↩︎

“Mainstream Buddhism” is proposed by Harrison (1995, 56) as a designation of non-Mahāyāna Buddhism, which was institutionally constituted by the dominant, established monastic orders in early Middle-Period India.↩︎

Schopen (2000, 20): “The opponents of the [Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā] are, then, monks who have entered ‘the well-taught Dharma and Vinaya,’ monks, presumably, of the established monastic orders among which the Mahāyāna apparently wants desperately to gain a foothold.” For passages against those opponents in the Aṣṭasāhasrikā, on which Schopen’s observation is based, see Mitra (1888, 59, 226, 429, etc.).↩︎

For the marginal status of the Mahāyāna in Middle-Period India, see Schopen (1979, 1–19) and (2000, 12–19), whose arguments are mainly buttressed by epigraphic evidence. An exceptional case is Nepal, where there are fifth- and sixth-century inscriptions that indicate high-level patronage of the Mahāyāna; see Acharya (2010, 23–75). For a different interpretation of the absence of epigraphic evidence pointed out by Schopen in light of the newly found Gāndhārī texts, see Allon and Salomon (2010, 17–18).↩︎

For the hypothesis of the migration of the Mahāyāna, see Schopen (2000, 24).↩︎

The Indo-Scythian missionary named Lokakṣema (fl. 168–186) was likely a walking encyclopedia that recited numerous texts from memory, although it is possible that he and his collaborators also utilized manuscripts in the form of birch-bark scrolls similar to the Gāndhārī Aṣṭasāhasrikā from the split collection (Falk and Karashima 2012, 2013). On the corpus of Mahāyāna sūtras translated by Lokakṣema, see Harrison (1993). For the life and work of Lokakṣema, see most recently Harrison (2018, 700–706).↩︎

Zürcher (1990, 176–81) attributed the relatively late emergence of residential monasteries in the Tarim Basin in part to the demographic upsurge and the development of agricultural techniques under Chinese influence. Although his observations (1990, 172–76) are based on archeological findings up to the 1980s, they still hold true today in overall terms. Neelis (2011, 7) rightly warns against the potential dangers of an overdrawn version of Zürcher’s notion of “long-distance transmission,” which does not fully account for regional and local transformations of Buddhism.↩︎

For the identification of the word as an honorary epithet adopted by kings after their enthronement rather than a royal surname as Chinese historians took for granted, see Wen (2016, 78–84).↩︎

See Neelis (2011, 297). Ruins of a temple in the shape of two concentric squares, which was originally made of a circumambulation path around a central shrine, were excavated in 2011 at a site in southern Domoko, which is nicknamed “the stump of a poplar tree” by Chinese archeologists. This site is radiocarbon dated to the end of the third century CE, and forms the earliest piece of evidence for Buddhist architecture in Khotan so far (see Wu 2013, 5). Whether the temple was part of a residential monastery remains unclear, and the issue of its original function is further complicated by the enigmatic mural paintings of nude celestial figures, which are yet to be identified and interpreted by art historians.↩︎

This is significantly different from the situation of Indian Buddhism in the Middle Period (first to fifth century CE), during which time the Mainstream monastic orders were most frequently the “recipients of gifts of land, monasteries, endowments of money, slaves, villages, deposits of relics and images” (Schopen 2000, 12–13), while Mahāyāna monks were “located within the larger, dominant, established monastic orders as a marginal element struggling for recognition and acceptance” (Schopen 2000, 20).↩︎

This work is not extant in its entirety, but the passage in question is quoted in the Fayuan zhulin 法苑珠林 ‘Pearl Grove in the Dharma Garden,’ a seventh-century encyclopedia of Chinese Buddhism; see T.2122, 53.491a21–28.↩︎

The ordeal by fire was foreign to the early Chinese world, where the oath and butting animals were used to resolve doubtful lawsuits and detect perjury; see MacCormack (1995, 71–93). But it was nothing unusual in ancient Iran, given the ritual efficacy ascribed to fire as the agent of Mithra in Zoroastrianism; see Boyce (1975, 69–76). For the story of the ordeal by fire that Ādurbād ī Mahrspandān, high priest of the Sassanian king Šabuhr II (r. 309–379), took on in order to prove the validity of Zoroastrian doctrine; see Tafażżolī (1983, 477). In this connection, it might also be of interest to note the late antique practice of book-burning as purification (Sarefield 2006; Herrin 2009), which only makes sense on the presumption that ‘pure’ scriptures survive the bonfire.↩︎

See Deeg (2006, 110) with special reference to this episode.↩︎

At the end of this passage from the Mingxiang ji, there is a brief remark to the effect that ‘Master Shi’ (shigong 釋公) reported this episode in detail (Campany 2012, 76) . This ‘Master Shi’ must be identified with the famous monk-scholar Dao’an (312–385), who was the first Chinese monk adopting the clerical ordination name Shi (i.e., Śākya). A register of miscellaneous sūtras with anonymous translators, attributed to Dao’an, makes reference to a work entitled ‘A Thorough Account of [Zhu] Shixing Sending the Larger [Prajñāpāramitā] (i.e., the Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā), in one fascicle’ (Shixing song Dapin benmo yi juan 仕行送大品本末一卷; T.2145, 55.18b25). This work, which had been accessible to Dao’an but was already lost in the early sixth century (Hayashiya 1941, 628), may have been the ultimate source of the narrative quoted above; see Z. Chen (2018, 105).↩︎

The concept of imaginaire that does not have the same connotations as ‘imaginary’ goes back to the School of Annales; see inter alia Duby (1975, 111–23), who defined it as the structural, ideational images that societies create. In the present context, I adopt imaginaire as a heuristic device to describe a stable and coherent assemblage of images and imaginations in relation to reality that are entrenched in a given society or socio-religious community sharing the same historical framework.↩︎

For the chronological problems of Faxian’s life, see Deeg (2005, 22–30).↩︎

For the Chinese text of the passage, see T.2085, 51.857b3–17 (ed. Zhang 1985, 13–14). See also the German translation by Deeg (2005, 511–12).↩︎

See Khotanese Gūmattīra, Tibetan ’Gum tir; see Thomas (1935, 19, n.3), Bailey (1951, 26), and Kumamoto (1982, 289). The second component of the monastery’s name -ttīra might be a lexeme of Khotanese origin which means ‘district’; see Thomas (1925, 262).↩︎

The Li yul lung bstan pa ‘Prophecy of the Li Country (i.e., Khotan)’ contains a legend according to which the monastery of Gomattīra was founded by a legendary Khotanese king Vijaya Vīrya whose reign, however, cannot be pinpointed in any historical source; see Emmerick (1967, 28–29).↩︎

For the occurrences of the monastery’s name in Dunhuang documents, see Kumamoto (1982, 289, n. 52). Those documents bear witness to the involvement of monks from this monastery in diplomatic missions during the late tenth century, as well as to their special ties with their royal patrons; see Zhang and Rong (1993, 284).↩︎

Martini (2013, 25) postulates “an ‘official’ introduction of Mahāyāna Buddhist institutions to Khotan,” which is not impossible. But it remains unclear what ‘official’ exactly means in this context. It is also questionable whether the institutions were introduced (from India?) or rather established in Khotan by way of local transformation.↩︎

For instance, Khotan, among a number of Chinese vassal states in the Tarim Basin, paid tribute in 335 to the Former Liang regime (320–376) as a token of surrender and allegiance; see (Loewe 1969, 96).↩︎

On the original name of the kingdom otherwise known in Chinese as shanshan 鄯善 vel sim., see Loukota (2020, 102–5).↩︎

For the Buddhist community in Caḍ̱ota and Kroraina during the given time period, see also Atwood (1991, 173–75) and Hansen (2012, 51–55).↩︎

This epithet applies to a cozbo (i.e., an official title apparently of Saka origin; see Tumshuqese cazba, Tocharian A cospā) named Ṣamasena, who was probably active in the late third century (Burrow 1940, 79, §390; Hansen 2004, 305); and to a king who is probably to be identified with Aṃgoka, also ruling in the third century, as is evinced in a Kharoṣṭhī inscription from Endere (Salomon 1999, 10–12). This epithet also glorifies the Kushan king Huviṣka (r. ca. 153/4–191) in some fourth-century Sanskrit fragments of a Buddhist narrative (avadāna), preserved in the Schøyen collection (Salomon 2002, 255–67). Despite the fact that the construction of Buddhist monasteries underwent a boom during the long reign of Huviṣka, there is no historical evidence for his conversion to the Mahāyāna. His family cult, in all likelihood, was Mazdeism, although he, like his father Kaniṣka, adopted a somewhat catholic attitude towards other religions; see Tremblay (2007, 84–88). For the occurrences of this term in early Mahāyāna sūtras, its semantics and nuances, see Harrison (1987, 76–77) and Nattier (2003, 209–10, n. 22).↩︎

For the Chinese text of the passage, see T.2085, 51.857a21–22 (ed. Zhang 1985, 8) . For an alternate translation of the passage, see Hansen (2012, 55) . See also the German translation by Deeg (2005, 508).↩︎